In a world that often demands perfection, especially when it comes to recovery, the story of Caitlyn Boardman—a mental health and sobriety advocate—is a powerful testament to the messy, non-linear reality of healing. As a guest on the Recoverycast podcast, Caitlyn shared her deeply personal journey through adoption trauma, the early loss of a parent, a turbulent relationship with alcohol and substances, and a complex interplay of mental health conditions, including Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and an eating disorder. Her path, marked by relapse, divorce, and the grief of losing both adoptive parents, is a striking example of persistence over perfection.

Her message, distilled from years of struggle and eventual triumph, offers a crucial anchor for anyone feeling lost: “Just to not give up hope. And that, you know, despite all the things life throws at you, there is hope on the other side, even when it feels like there is none at all.” Caitlyn’s willingness to embrace the imperfections of her journey—from being the “girl with the alcohol in her closet” to a public advocate—shows that true strength lies not in avoiding the fall, but in constantly choosing to get back up. This comprehensive article delves into the core challenges Caitlyn faced and builds on her story to offer 12 critical takeaways for navigating co-occurring disorders, trauma, and the continuous fight for a better life.

1. Recognizing the Indirect Impact of Childhood Trauma and Adoption

Caitlyn’s childhood, while seemingly stable, was underpinned by the indirect trauma of early life experiences. Adopted from South Korea and raised in a white family, she initially believed her adoption didn’t affect her. It wasn’t until she reached adulthood and sought therapy that the deeper emotional roots of her struggles began to surface.

Caitlyn’s therapist posed a critical question that unlocked a deeper understanding: “You’re adopted, but where were you the first four months of your life?” This led to the discovery that she had been in a foster home, a separation that her therapist linked to her adult trust issues. This experience highlights a crucial aspect of trauma: it doesn’t have to be a direct, dramatic event to leave a lasting impact. The pre-verbal separation from her birth mother and subsequent placement created an emotional blueprint that affected her ability to form secure attachments later in life.

Compounding this was the loss of her adoptive father at the tender age of six. She recalls: “I remember running away as a kid. I was just really upset and my mom, she let me cry, but you know, then it was just, we never really talked about it.” The lack of open communication about grief meant that she and her brother “suffered in silence,” a common experience in families where emotional expression is suppressed.

Explore trauma treatment options.

2. Early Onset Alcoholism and the Search for Numbing

The seeds of addiction were planted early for Caitlyn, fueled by a combination of easy access to alcohol and an internal struggle to cope with her feelings of loneliness and grief. She recounts starting to drink around age 13 and drinking alone. Access was made easy because her mother kept alcohol in the house “all the time.”

Her habit quickly progressed from experimentation to a pattern of isolation and concealment: “I remember I would take alcohol from my mom, I’d put it in water bottles… and stuff it in my closet. Like my friends used to joke around, like they’d be like, oh, you’re the girl with the alcohol in her closet.” This early reliance on alcohol to numb difficult emotions is a classic red flag for a developing substance use disorder.

The interviewer rightly pointed out the heartbreaking realization in hindsight: “That’s a kid really struggling, grabbing for alcohol and substance to try and numb that, that’s extremely tough.” This pattern of self-medication would continue for years, culminating in a period where she felt destined to suffer: “I feel like I’m meant to suffer. So that’s why I drank. I was like, I, I feel like I’m just not meant to be happy.” This belief—that she was unworthy of happiness—drove her substance use, highlighting the deep connection between self-worth and addiction.

3. Navigating the Complexities of Co-Occurring Disorders

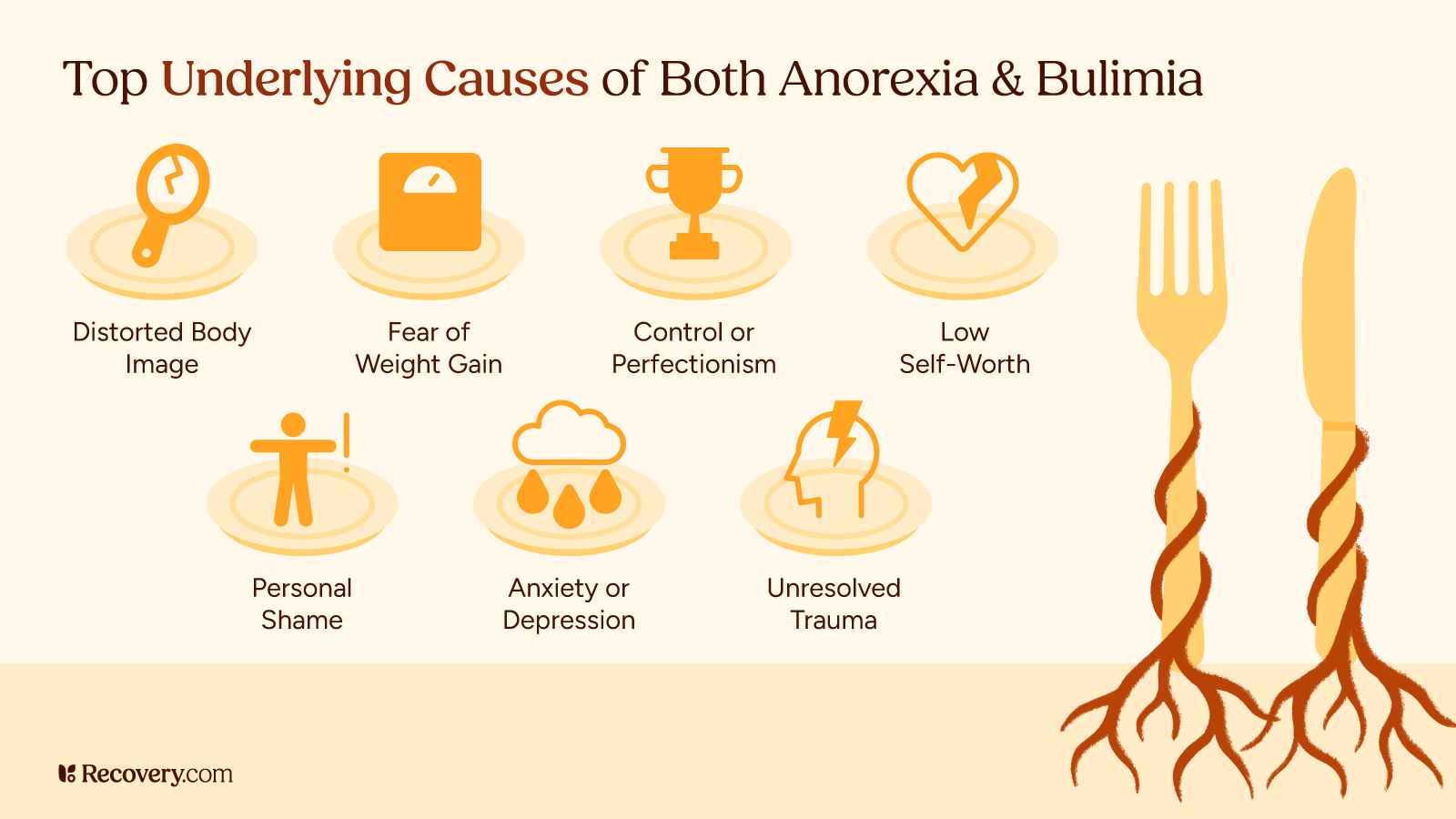

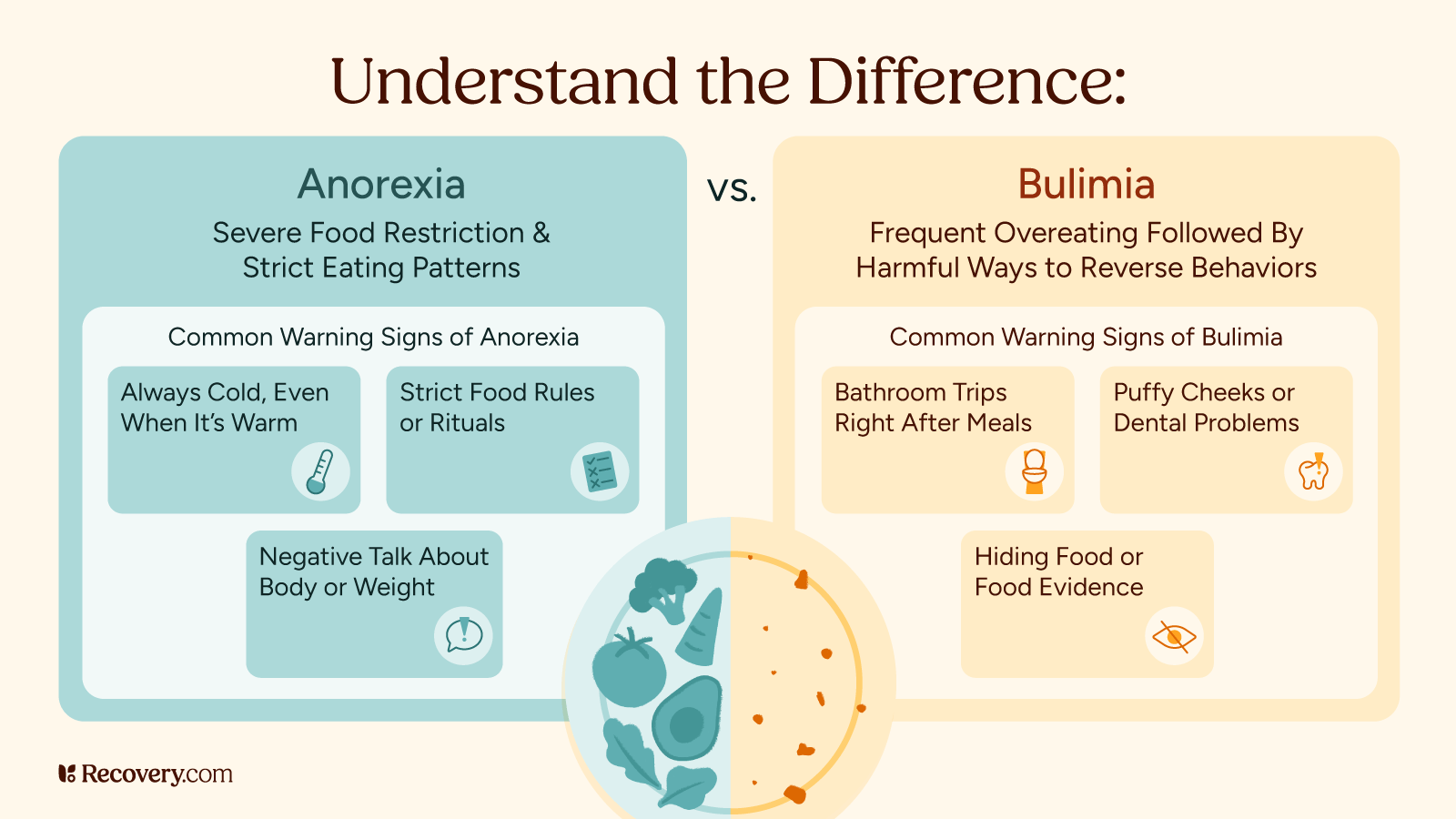

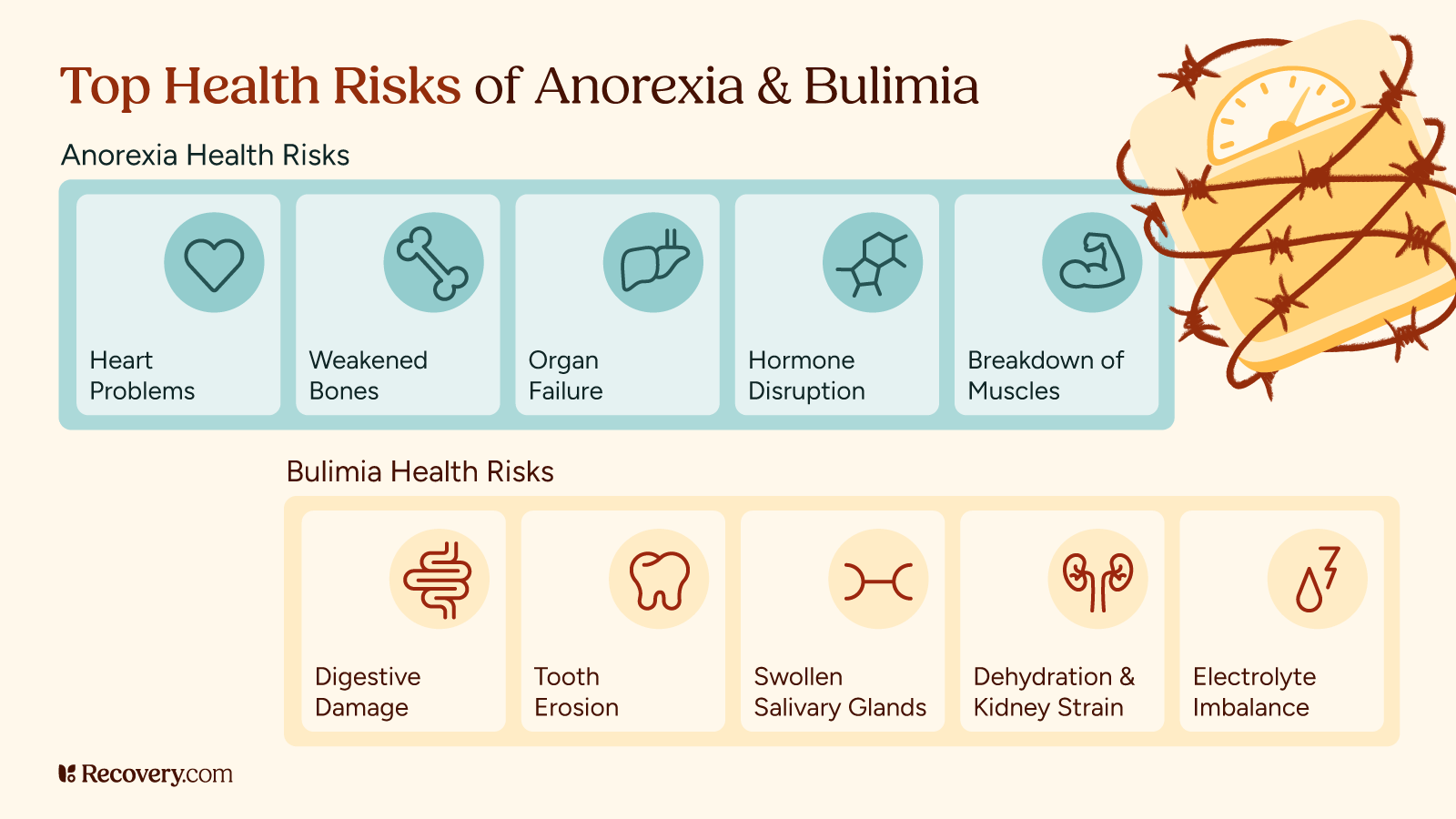

Caitlyn’s journey is a powerful case study in comorbidity, or the co-occurrence of substance use disorders with mental health conditions. She battled alcoholism alongside an eating disorder and was later diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD).

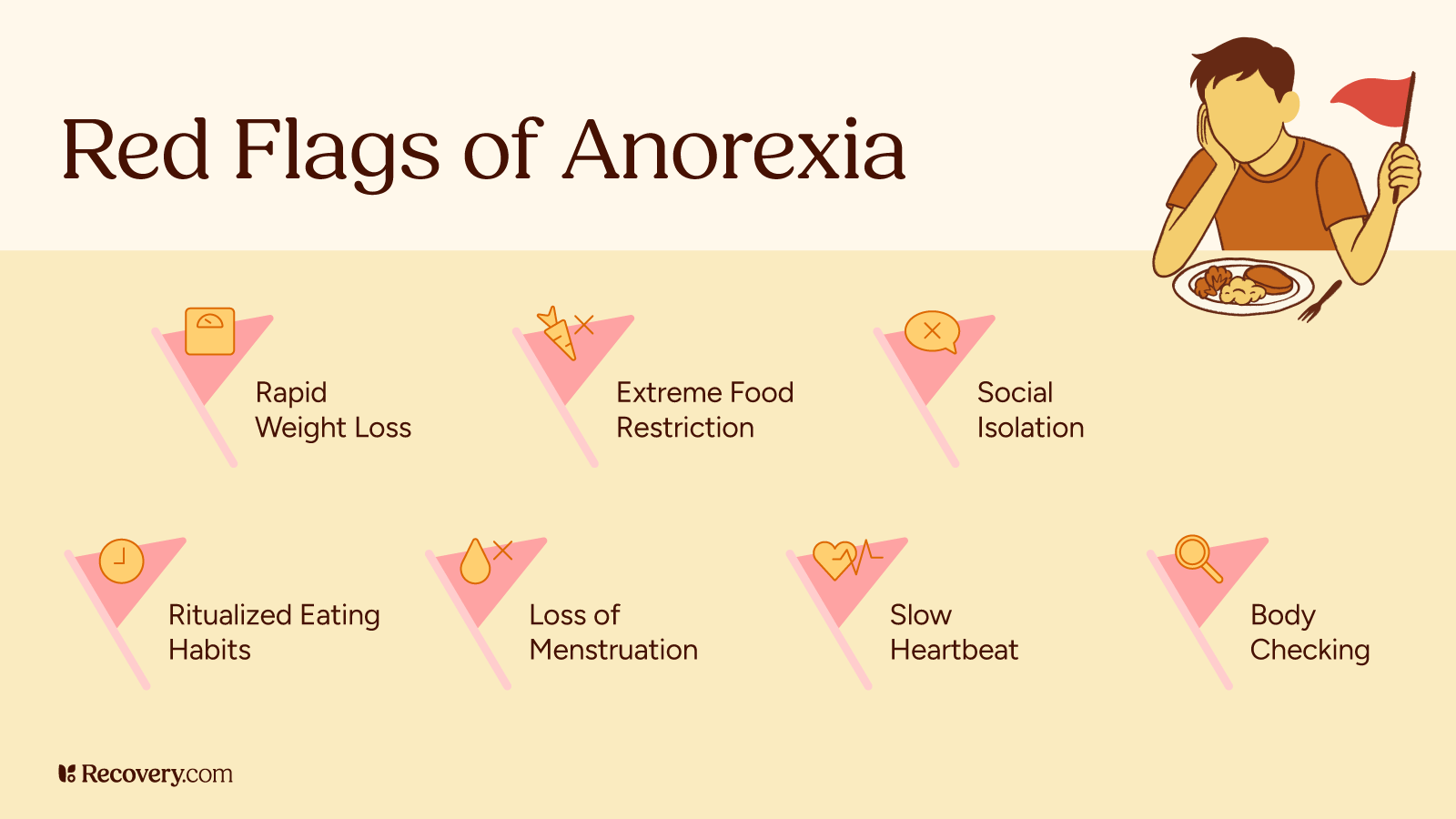

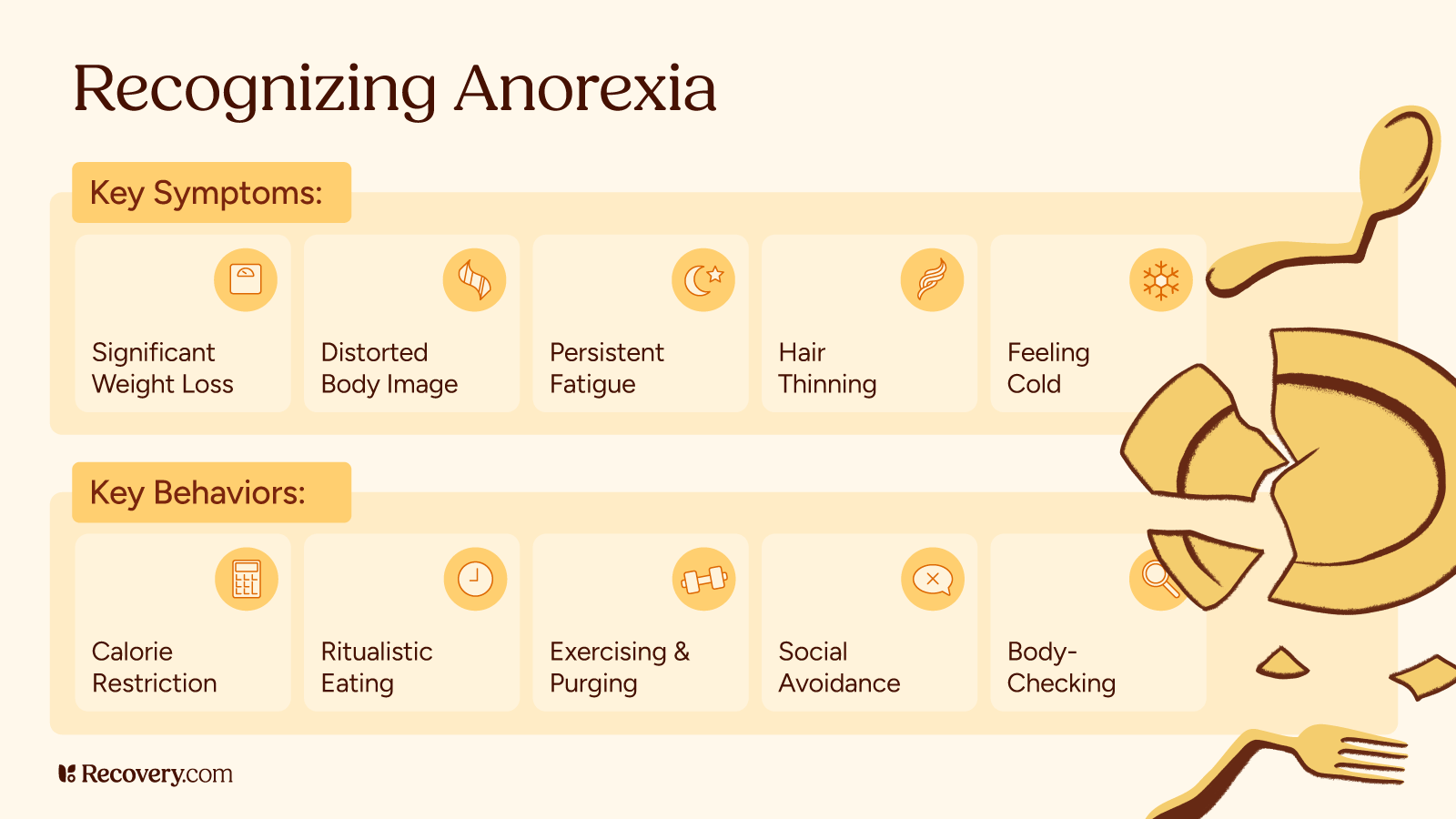

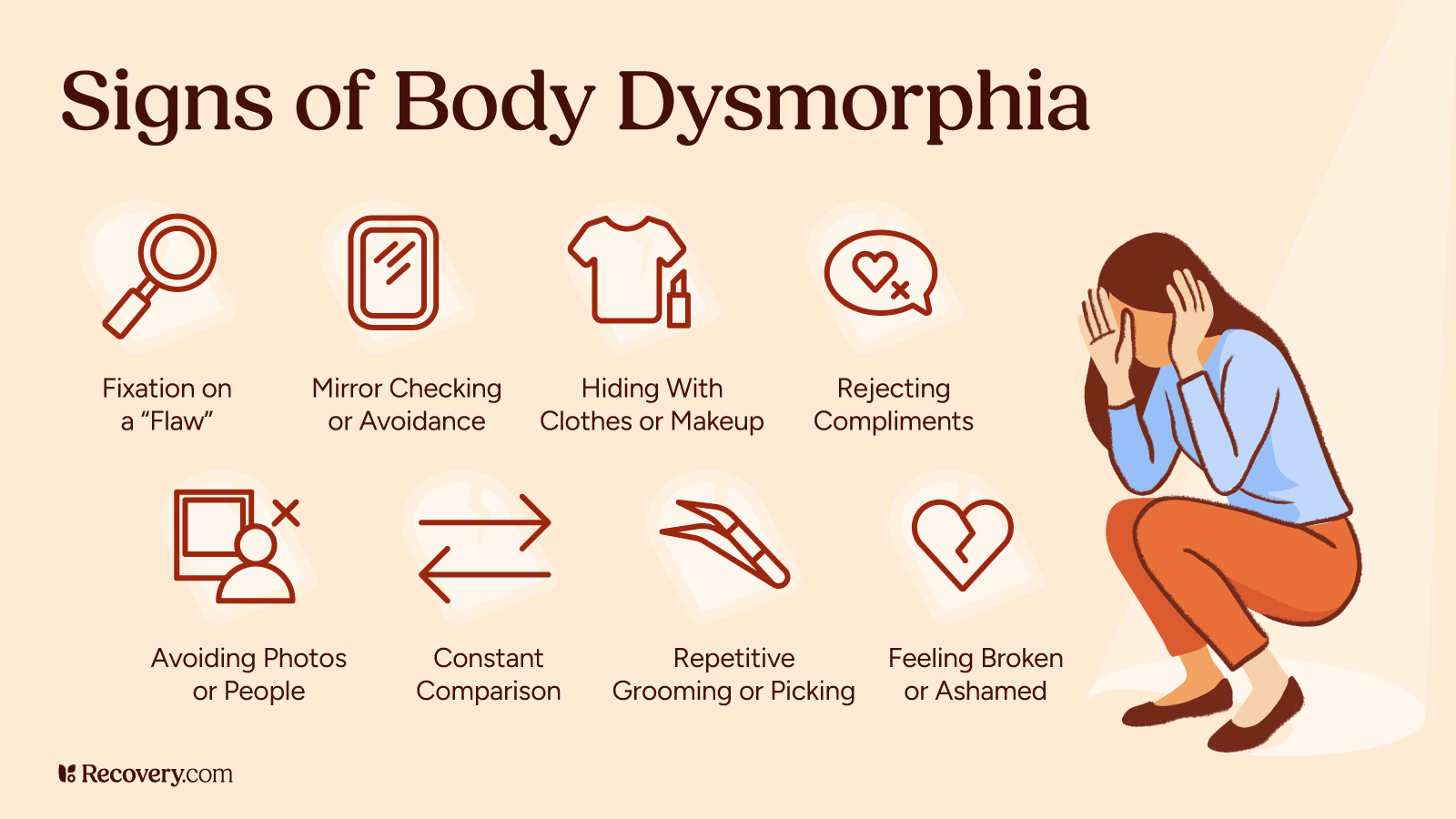

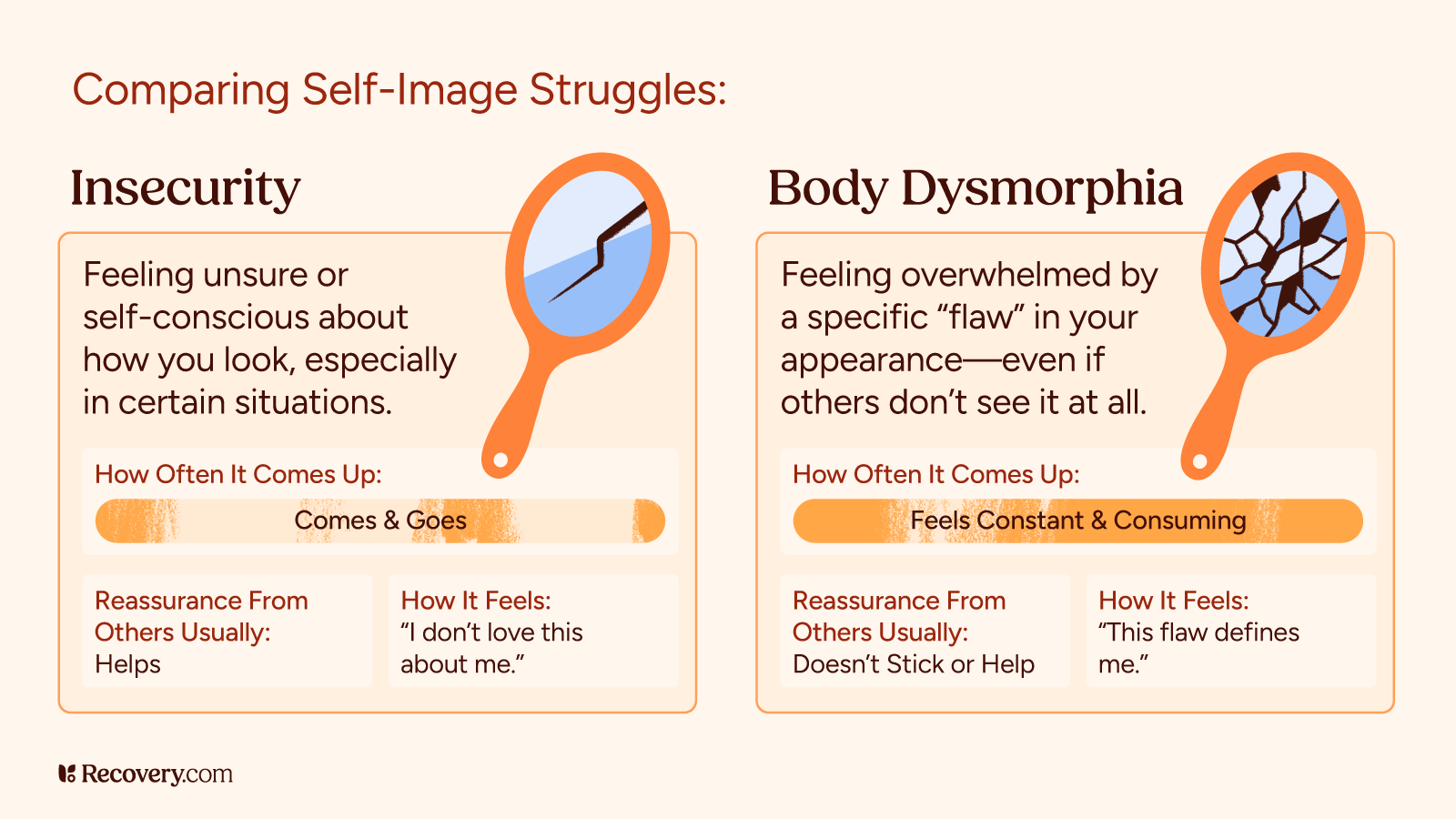

The Eating Disorder and Body Image

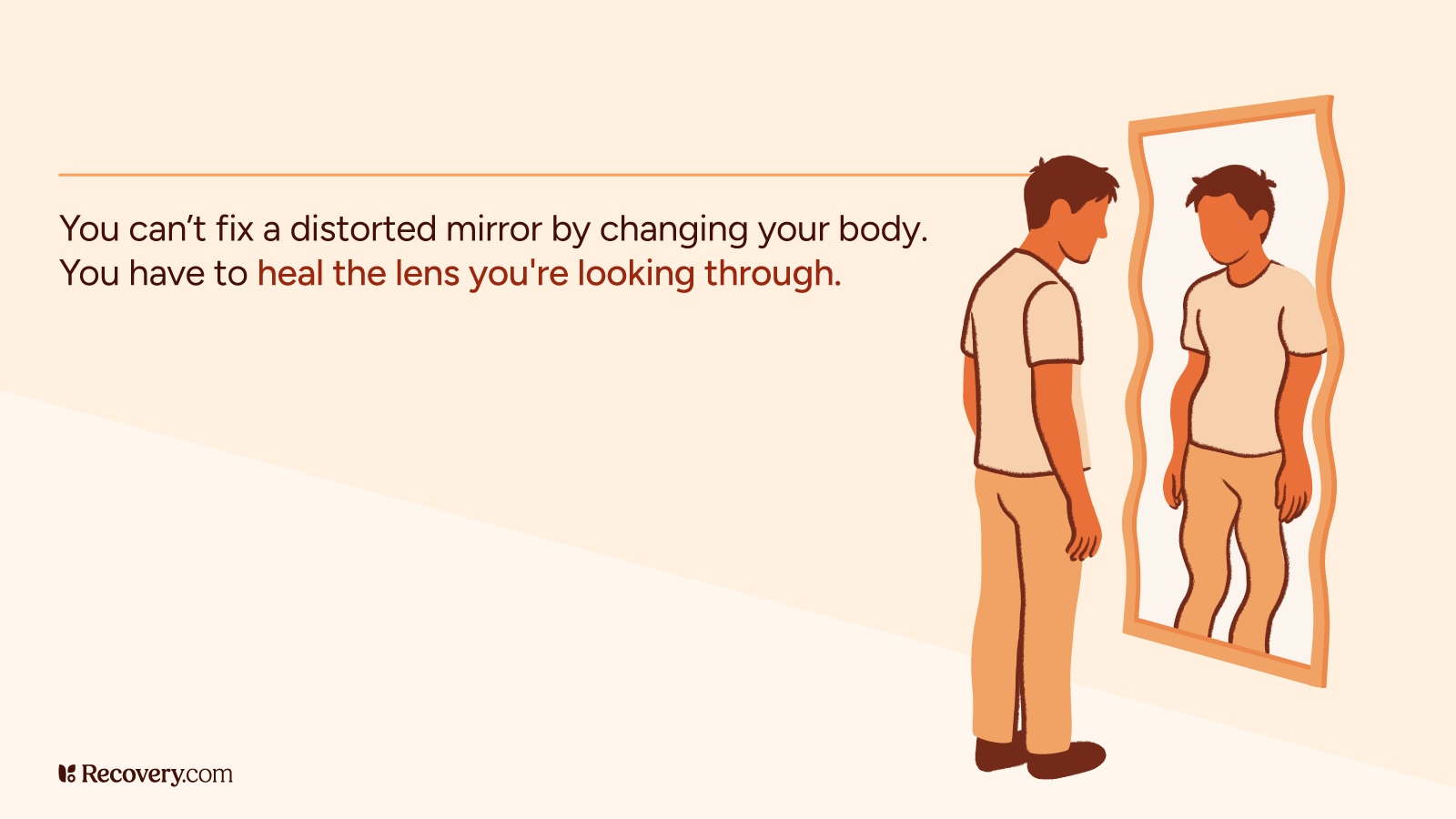

Her struggle with the eating disorder intensified after having her children, driven by a hyper-focus on weight loss. This pursuit of “skinny” led to severely restrictive behaviors, eventually causing her to view herself as overweight even at a critically low weight of 98 pounds. This distorted self-perception is a hallmark of eating disorders, where the underlying issue is not truly about food or weight, but about control, self-criticism, and emotional regulation.

See eating disorder treatment options.

The Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) Diagnosis

Caitlyn pursued psychiatric help after feeling “off” her whole life due to severe mood swings. She was diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), a condition that the clinician linked directly to her trauma. BPD is characterized by unstable moods, behavior, relationships, and self-image, often leading to impulsive behavior, intense emotional responses, and difficulties with secure attachments—all of which factored into Caitlyn’s self-destructive patterns. The self-harm that started in middle school evolved into physically hitting and bruising herself, particularly when alcohol was involved, demonstrating the volatile synergy between her substance use and mental health struggles. She noted that BPD, unlike some other disorders, “you get it from trauma.”

4. The Deepening of Addiction and Rock Bottom

The full severity of Caitlyn’s addiction surfaced after her third child, following a messy breakup with the children’s father. The intermittent drinking of her early motherhood quickly escalated to drinking “all day, every day”. The day-to-day struggle was marked by extreme self-harm and an inability to maintain stability. She lost one job and narrowly avoided being fired from another after showing up to work “blackout drunk” and messing up “every table’s order.”

The turning point—or “rock bottom”—was a dramatic, frightening moment in 2021, a month after the birth of her fourth child. A volatile argument with her partner while both were drinking led to a frightening climax that resulted in the police being called for the third time. The police’s warning about the potential involvement of Child Protective Services served as a stark and terrifying wake-up call.

Find integrative alcohol addiction treatment options.

5. Choosing Sobriety and Embracing New Habits

After the incident with the police, Caitlyn embarked on her recovery journey. Despite having no formal treatment or therapy at the time—a testament to her sheer willpower and underlying resilience—she stopped drinking daily. She noted that while she didn’t experience the severe physical withdrawals many do, she was immediately plagued by intense cravings, which often manifest as a craving for sweets in early sobriety.

To fill the void left by alcohol, she actively jumped into new habits and tools:

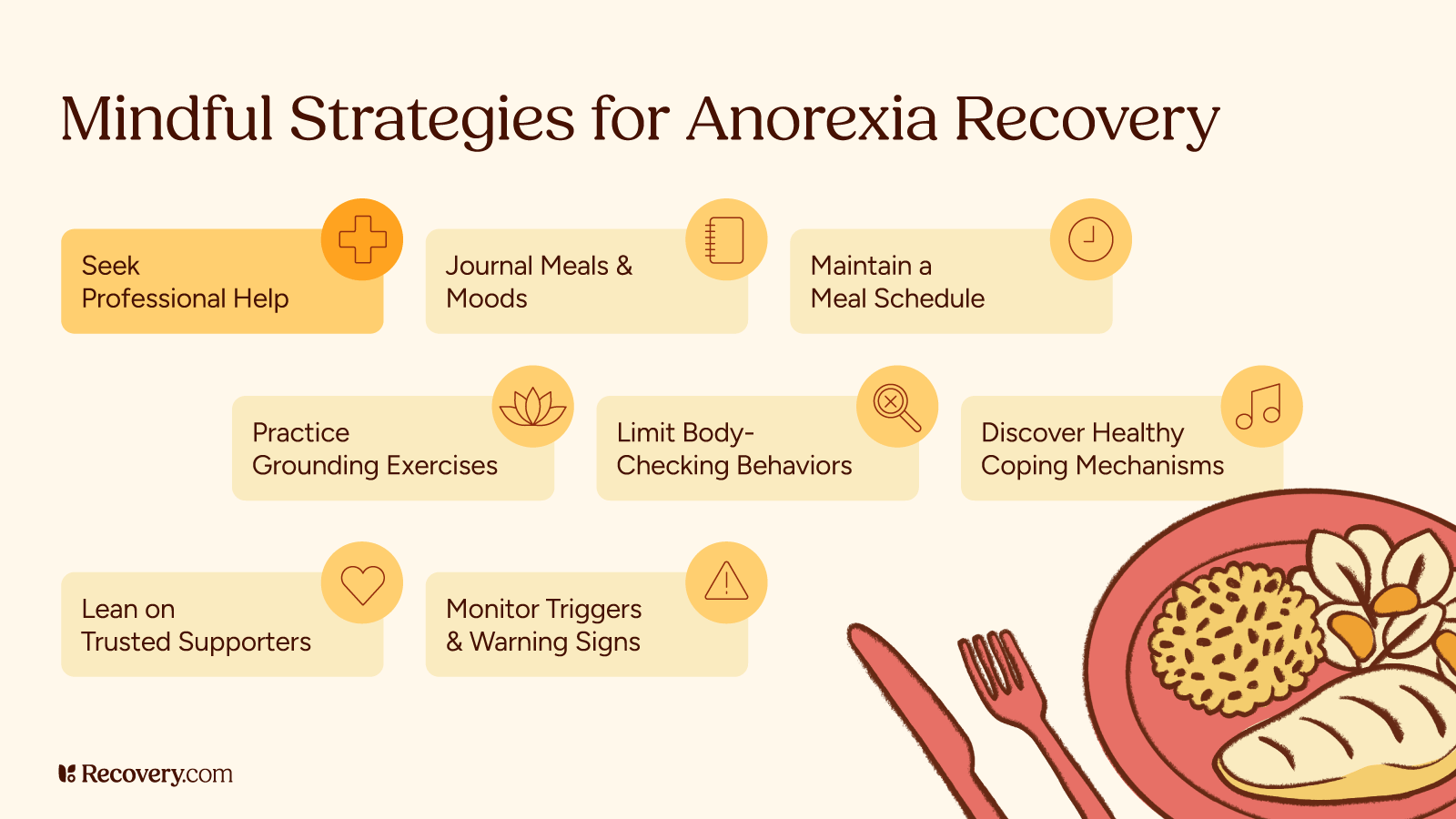

- Fitness Shift: She completely changed her focus in the gym, moving from working out “to be skinny” to working out “to be strong, not skinny.” This complete mindset switch reflected a fundamental move toward self-care and health, resulting in a healthy weight gain of 15 pounds.

- Mindfulness and Meditation: Overcoming the initial difficulty of sitting with a “sober brain” and a head full of trauma-driven thoughts, she credits meditation as a “key to so many things,” especially for managing her BPD symptoms. She also highlighted the importance of breathwork to calm her nervous system in daily situations.

6. The Necessity of Environmental and Relational Changes

Maintaining sobriety demanded a complete overhaul of her social life. Since her entire friend circle drank, she had to stop going out, which inevitably led to losing many friends. While this loss hurt, she adopted a mature perspective: “I was like, you know what? They weren’t my friends in the first place.” This realization is a vital lesson in recovery: true friends support your health, while drinking companions only support the addiction.

This principle was painfully tested in her marriage, which had begun and was largely fueled by alcohol during the COVID-19 pandemic. She eventually found herself navigating a divorce from a partner who repeatedly lied about his own sobriety. “I found out later on that he had drank and lied to me about it… that was hard to deal with.” The pain and harassment from the dissolution of that toxic relationship made her “want to drink so bad,” but she persevered.

The anchor that kept her from drinking during the immense stress of divorce and the grief of her mother’s passing was her children. She intentionally chose to provide them with a different, more emotionally available experience of grief than the one she had as a child: “I wanted to be strong for them. And, you know, not go down that dark path.”

7. The Power of Advocacy and Vulnerability on Social Media

In an age where public figures often curate perfect narratives, Caitlyn’s decision to share her raw journey publicly has been a source of healing and connection. Starting with a single TikTok post about being “one month sober” in 2021, her vulnerability resonated with a massive audience.

What’s interesting is the contrast she found in sharing: she describes herself as a private person in her day-to-day life, yet an “open book” on social media. This distinction is common for advocates who find safety and connection in a digital community. The feedback and messages she received affirmed that her story was making a difference, transforming her personal struggle into a source of public hope.

8. Understanding the Nature of Relapse: A Non-Linear Journey

Caitlyn’s most recent experience highlights a key message: recovery is not linear, and relapse is often a process that begins long before the first drink is taken.

In a situation that many in sobriety fear, she was mistakenly served a full-alcohol beer instead of the non-alcoholic (NA) beer she ordered. While she noticed the strong taste, she initially rationalized it. Her therapist offered a profound concept: “Relapse before you relapse.” Caitlyn realized that for a month beforehand, she had been “looking for something,” having bought and kept a miniature bottle of liquor in her fridge. This pre-relapse mental softening meant that the accidental exposure became a justification: “I was like, gotcha. This is the perfect opportunity. You know? You were justifying in your head.”

The Three-Day Wake-Up Call

The accidental slip quickly spiraled into a full, short-lived relapse. The severity of the incident—which involved her being so drunk she ended up in the hospital after friends reported her banging her head on the floor—served as a definitive reminder of where her addiction leads. After a brief period of continued drinking for three days, the physical illness from dehydration and the shame of the behavior quickly brought her back to the clarity of sobriety: “This is not it. Like we didn’t do this. We can go back now.”

The non-linear nature of recovery means a slip doesn’t erase the progress made. It’s a data point, not a destination.

9. The Importance of an Open Dialogue on Grief

The most moving part of Caitlyn’s story is the conscious choice to heal her own past by changing her present and future. Reflecting on the silent suffering after her father’s passing, she made a deliberate choice to be “very open” with her children following the loss of her adoptive mother: “I was like, we need to talk about it.”

This act of providing emotional space for her children is profoundly healing. As she put it, “It feels really good to be able to like, have those tools from that experience to like give that to my kids while they’re going through this.” This breaks the generational cycle of emotional avoidance and is a powerful act of self-compassion directed at the child version of herself.

10. The Simple Power of Persistence

Caitlyn’s entire narrative is summed up by her core message: persistence. She didn’t have a magical, instant recovery. She battled on and off for years, from her early teens until she got sober in 2021, a five-year period of severe struggle after her third child. Her persistence was not a sudden burst of perfect effort, but the quiet, daily commitment to “keep fighting every day, kept showing up until one day I was like, I’m sober.”

This relentless showing up, even when things felt utterly hopeless, is the essence of her success. For anyone feeling overwhelmed by the length and difficulty of their own recovery journey, Caitlyn’s story is proof that showing up for yourself is the single most important action you can take.

11. The Protective Role of Parenthood in Sobriety

While a challenging relationship with her children’s father fueled some of her heaviest drinking, her children ultimately became her most powerful protective factor. When faced with the immense grief and stress of her mother’s passing, they were her anchor, keeping her from drinking.

She is honest about this reality: “I feel like if I didn’t have my kids, I probably would’ve drank.” For many parents, the desire to provide a stable, loving environment becomes the “reason” that outweighs the addiction’s pull. It transformed her motivation from self-loathing (“I’m meant to suffer”) to service (“I wanted to be strong for them”).

12. Never Give Up Hope: A Final, Powerful Word

Caitlyn’s journey from a self-harming, isolated child with a hidden stash of alcohol to a strong, vulnerable mother and advocate is a roadmap for those navigating the darkest of paths. Her entire message hinges on this simple, profound instruction: Don’t give up hope.

The most compelling quote from her experience encapsulates the dark mental state of addiction and the breakthrough of recovery: “I’ve been in such a dark place, I’ve been like that in that area of my life where I’m like, things will never get better. I’ll never be happy… And that’s why I kept drinking.” Her eventual turn—the decision to keep fighting despite this deep-seated belief—is the persistence that turned her life around.

Her story is a living example of a fundamental truth: no matter how complex the mental health issues (BPD, eating disorder, alcoholism, trauma) or how difficult the circumstances (loss, divorce, relapse), the persistence to show up every day leads to the other side. Healing is messy, but it is always possible.