We all have worries and routines. But when unwanted thoughts or repetitive behaviors begin to take over your mind and disrupt your life, it may be time to ask: Could it be obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)?

An OCD test is a self-assessment tool designed to help you reflect on your mental patterns and determine whether they align with the symptoms of OCD. It doesn’t diagnose, but it can offer clarity. It’s a starting point for those wondering whether their distressing habits, thoughts, or routines may be signs of something deeper.

Disclaimer: This tool is not a diagnosis. It is meant to help you reflect and identify if further support may be helpful. If you’re concerned about your results, speak with a licensed mental health professional or healthcare provider.

Why Take an OCD Self-Assessment?

Many people live with obsessive thoughts or engage in compulsive behaviors without realizing that their experiences fit the clinical picture of OCD. Because of stigma or misunderstanding, symptoms often go untreated for years.

Taking a self-assessment can help you:

- Recognize patterns that align with OCD symptoms

- Clarify whether your thoughts or behaviors are part of a larger mental health condition

- Identify how much time, energy, and distress these patterns create in your daily life

- Decide whether it’s time to seek formal evaluation, diagnosis, or OCD treatment

Understanding your experience is a powerful first step. This test can offer a language for what you’re going through and guidance for what comes next.

What Is Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder?

Obsessive-compulsive disorder is a type of anxiety disorder characterized by two main components:

- Obsessions: recurring, distressing, and often intrusive thoughts (e.g., fear of contamination, fear of harming others, or religious guilt)

- Compulsions: repetitive behaviors or mental rituals performed to neutralize or reduce the anxiety caused by the obsessions (e.g., excessive hand washing, checking locks, counting)

The DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) lists OCD as a diagnosable mental illness when these thoughts and actions are time-consuming, distressing, and interfere with your ability to function.

People with OCD often know their thoughts are irrational, but the compulsive cycle can feel impossible to break.

Common Symptoms of OCD

Symptoms of OCD vary from person to person, but most involve a pattern of obsession, distress, and temporary relief through compulsion.

Some examples include:

- Constant fear of contamination leading to hours of hand washing

- Intrusive thoughts about harming a loved one, followed by avoidance or mental rituals

- Needing items arranged “just right” to reduce anxiety

- Counting steps, tapping, or praying to prevent a feared event

- Excessive checking (doors, appliances, locks)

- Avoiding certain people, objects, or places due to specific obsessive thoughts

These behaviors often go unnoticed by others, but for the person struggling, they can dominate every moment of the day.

How the Online OCD Test Works

An online OCD test typically includes a questionnaire that screens for common obsessive and compulsive patterns. It may ask:

- How often do you experience unwanted thoughts you can’t control?

- Do you feel compelled to perform certain rituals or behaviors to ease distress?

- Have these behaviors become difficult to stop, even when you try?

- Are these patterns interfering with your relationships, work, or well-being?

Your answers help assess whether your symptoms match those of OCD or a related disorder and whether professional evaluation may be helpful.

What If You Score High on the OCD Test?

A high score on a self-assessment may suggest a possible mental health disorder, but it is not a clinical diagnosis. Still, your score can be a wake-up call.

Here’s what you can do next:

- Speak with a licensed mental health professional who can conduct a full assessment.

- Ask about CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy) and ERP (exposure and response prevention)—the gold standard for treating OCD.

- Consider medication options like SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), often prescribed to help manage OCD symptoms.

- Explore local or virtual support groups to connect with others facing similar challenges.

- Educate yourself about treatment options, recovery timelines, and how OCD may co-occur with conditions like autism or other mental health disorders.

Early treatment can greatly improve your quality of life and reduce the impact of OCD on your day-to-day functioning.

What OCD Can Look Like in Daily Life

To understand the impact of OCD, it helps to consider real-world examples:

- A college student spends four hours a night checking their homework repeatedly to avoid making a mistake, leading to sleep deprivation and poor grades.

- A new parent avoids holding their baby because they fear having a violent thought—despite never acting on it.

- A young teen avoids social situations and hand washing rituals take over their school day.

In these cases, the fear is not the problem. It’s the cycle of obsession and compulsion that traps the person in distress.

OCD and Related Disorders

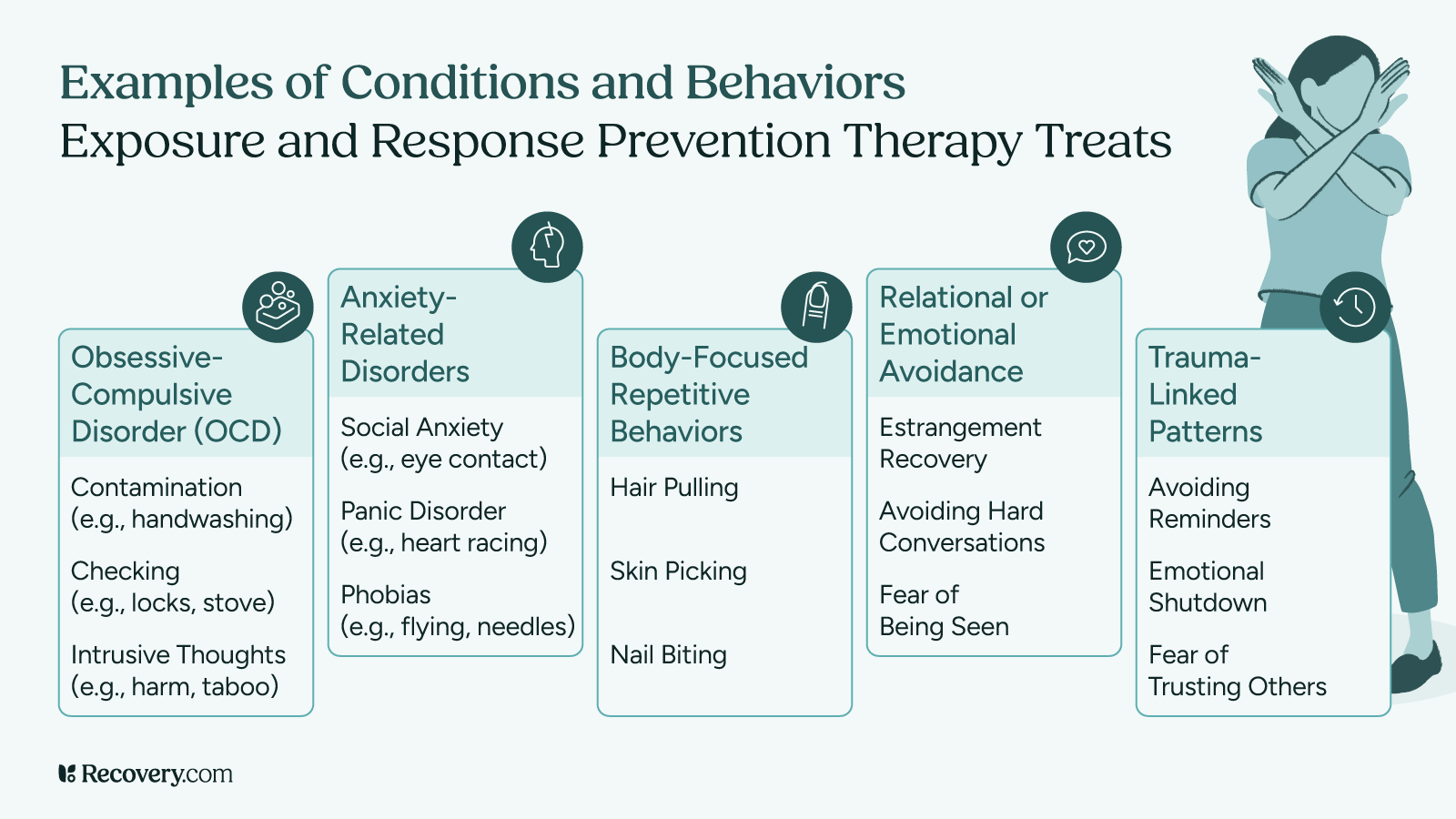

OCD shares features with several related disorders, including:

- Hoarding disorder

- Body dysmorphic disorder

- Skin-picking (excoriation) and hair-pulling (trichotillomania) disorders

- Obsessive-compulsive symptoms in individuals with autism spectrum disorder

These conditions can also be treated, and often respond to similar treatment options as OCD.

What the OCD Test Can—and Can’t—Tell You

What it can do:

- Highlight symptoms consistent with OCD

- Help you reflect on your mental habits and patterns

- Motivate you to seek care if your well-being is being affected

What it can’t do:

- Replace a clinical diagnosis from a mental health professional

- Determine what type of OCD or related disorders you may have

- Account for your full psychological history or trauma background

Self-assessments are powerful tools, but they are most effective when followed by a conversation with a clinician.

Who Should Take the OCD Test?

You might consider taking the test if you:

- Experience obsessive thoughts or compulsive behaviors that interfere with work, school, or relationships

- Feel exhausted by your need to repeat certain actions or avoid specific triggers

- Suspect your thoughts or behaviors are more than just anxiety or routine

- Have a family member or loved one expressing concern

- Want to understand more about mental health conditions that impact your functioning

If any of this resonates, the test can be a safe place to begin.

Treatment That Works for OCD

OCD is treatable. Many people go on to live full, connected, and joyful lives after diagnosis and treatment.

The most effective approaches include:

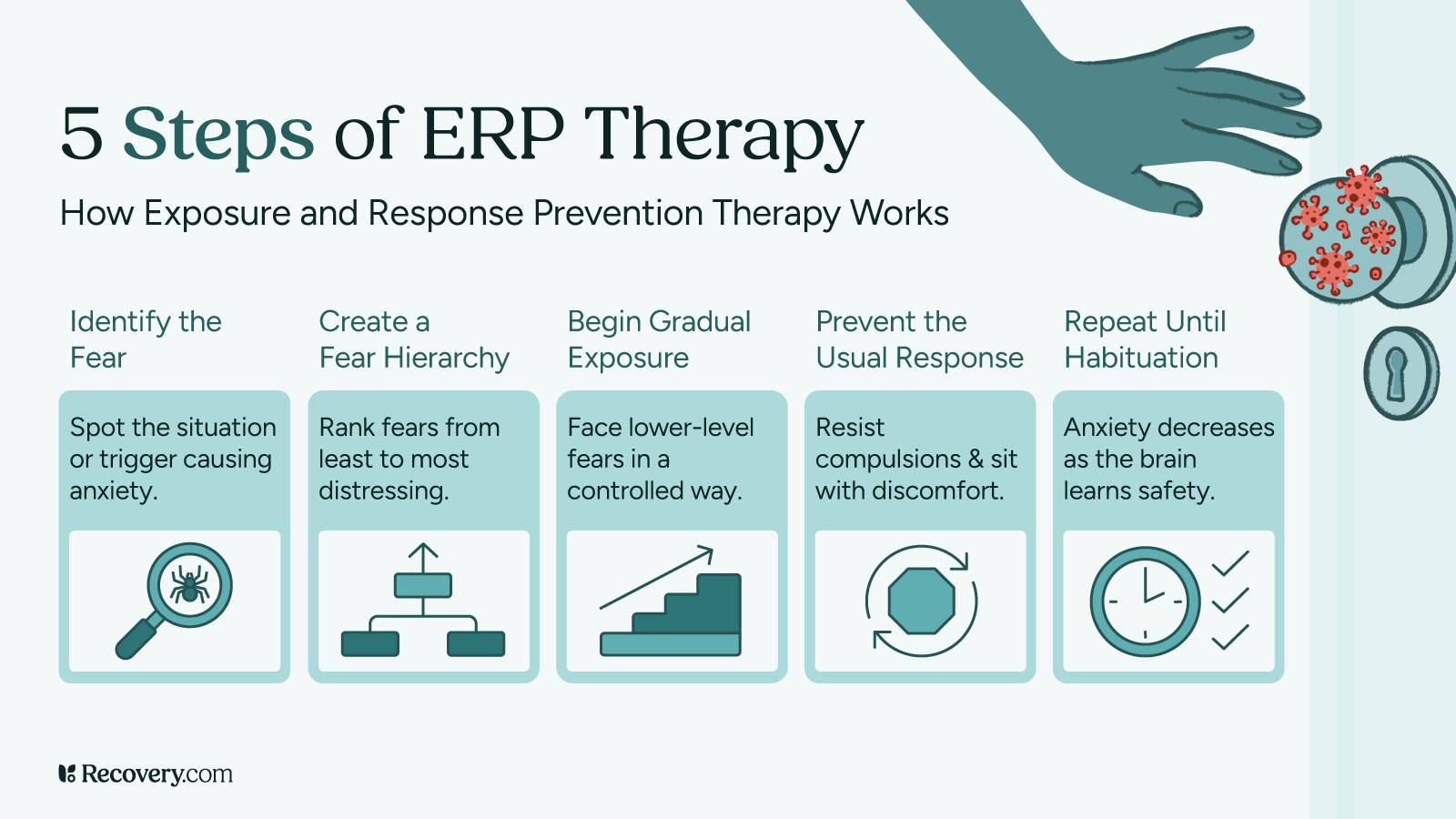

- Exposure and response prevention (ERP): Helps reduce fear by gradually facing obsessions without engaging in compulsions

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT): Teaches tools to identify and challenge obsessive thinking patterns

- SSRIs: A class of antidepressants that can reduce symptoms by altering serotonin levels in the brain

- Talk therapy to process trauma or shame related to OCD symptoms

- Peer-led support groups to build connection and reduce isolation

In more complex cases, intensive treatment programs or collaboration with psychiatry may be needed.

If you’ve been battling constant doubts, rituals, or fears that just won’t go away, you’re not weak, and you’re not alone. The OCD test is a tool for awareness, not diagnosis. But that awareness can lead to hope, treatment, and freedom.

OCD doesn’t define you. With the right support and interventions, life can become more spacious, grounded, and your own again.

Resources and Next Steps

- Obsessive compulsive disorder treatment center near you

- How Much Does Rehab Cost?

- What Kind of Treatment Do I Need? Understanding Levels of Care for Addiction and Mental Health Treatment

External Resources:

- International OCD Foundation (IOCDF)

- National Institute of Mental Health – OCD Overview

- Anxiety & Depression Association of America – OCD Resources

FAQs

Q: Is OCD the same as being neat or organized?

A: No. OCD is a mental illness, not a personality trait. While some people associate OCD with cleanliness, the condition is defined by obsessions and compulsions that cause distress and interfere with life.

Q: Can I have OCD without visible compulsions?

A: Yes. This is often called “Pure O” OCD, where compulsions are mental rather than physical. People may perform mental rituals, such as praying or repeating phrases silently.

Q: Is OCD caused by low serotonin?

A: Serotonin may play a role, but OCD has complex causes, including genetic, neurological, and environmental factors. SSRIs can help by regulating serotonin levels in the brain.

Q: Can adolescents have OCD?

A: Absolutely. OCD often begins in childhood or adolescence. Early signs may include ritualistic behavior, intense worries, or a sudden change in daily function.

Q: Does everyone with intrusive thoughts have OCD?

A: Not necessarily. Many people have intrusive thoughts occasionally. With OCD, these thoughts become frequent, distressing, and lead to compulsive behaviors meant to neutralize them.

Q: How long does OCD treatment take?

A: It varies. Some people see improvement in weeks, while others benefit from longer-term therapy. The key is a consistent, personalized treatment plan guided by a mental health professional.