Addiction can feel like an unending cycle of pain, disappointment, and desperation, not only for the person struggling but also for their loved ones. For many, the focus is on the substance itself—the alcohol, the pills, the cocaine—and the frantic search for a way to stop using. However, as recovery advocate Sam Davis explains, this approach often misses the core of the problem. In a recent podcast, Davis shared his personal story, revealing that the true battle isn’t with the substance but with the underlying emotional pain, mistaken belief systems, and traumatic experiences that drive a person to seek escape.

Davis’s journey from a childhood marred by trauma and low self-esteem to a life of peace and freedom offers a powerful testament to the idea that addiction is not a moral failing but a result of deep-seated pain. He found that true healing came not from simply abstaining from drugs but from doing the difficult internal work of rebuilding his life’s foundation. Through his story, Davis offers a new perspective on addiction, one that shifts the focus from the symptoms to the root cause, providing hope and a clear path forward for those who are struggling.

1. Addiction Is a Result of a Problem, Not the Problem Itself

When we see someone struggling with addiction, our natural instinct is to focus on their substance use. We might blame them for their choices, plead with them to stop, or try to control their access to drugs or alcohol. But Davis argues that this approach is fundamentally flawed because it ignores the deeper issue. “I would hope that people would take away the fact that addiction is just a result of a problem,” Davis states, “a problem of pain, emotional, mental crisis, and that we all struggle with addictions to something.” He emphasizes that the real focus should be on treating the pain, not just the behavior that results from it.

Davis’s personal story illustrates this point perfectly. His addiction wasn’t the result of a desire to be reckless; it was a desperate attempt to cope with profound emotional turmoil that began in childhood. He explains that he was “really in recovery from the mistaken belief systems” he had developed over a lifetime. These beliefs—that he was “faulty,” “dirty,” and had no value—were the true problems. The drugs were simply his temporary, and ultimately destructive, solution to a pain he didn’t know how to handle. This perspective encourages a more compassionate and effective approach to treatment, one that seeks to understand and heal the individual’s core pain rather than just managing their substance use.

2. Childhood Trauma Can Lay the Foundation for Addiction

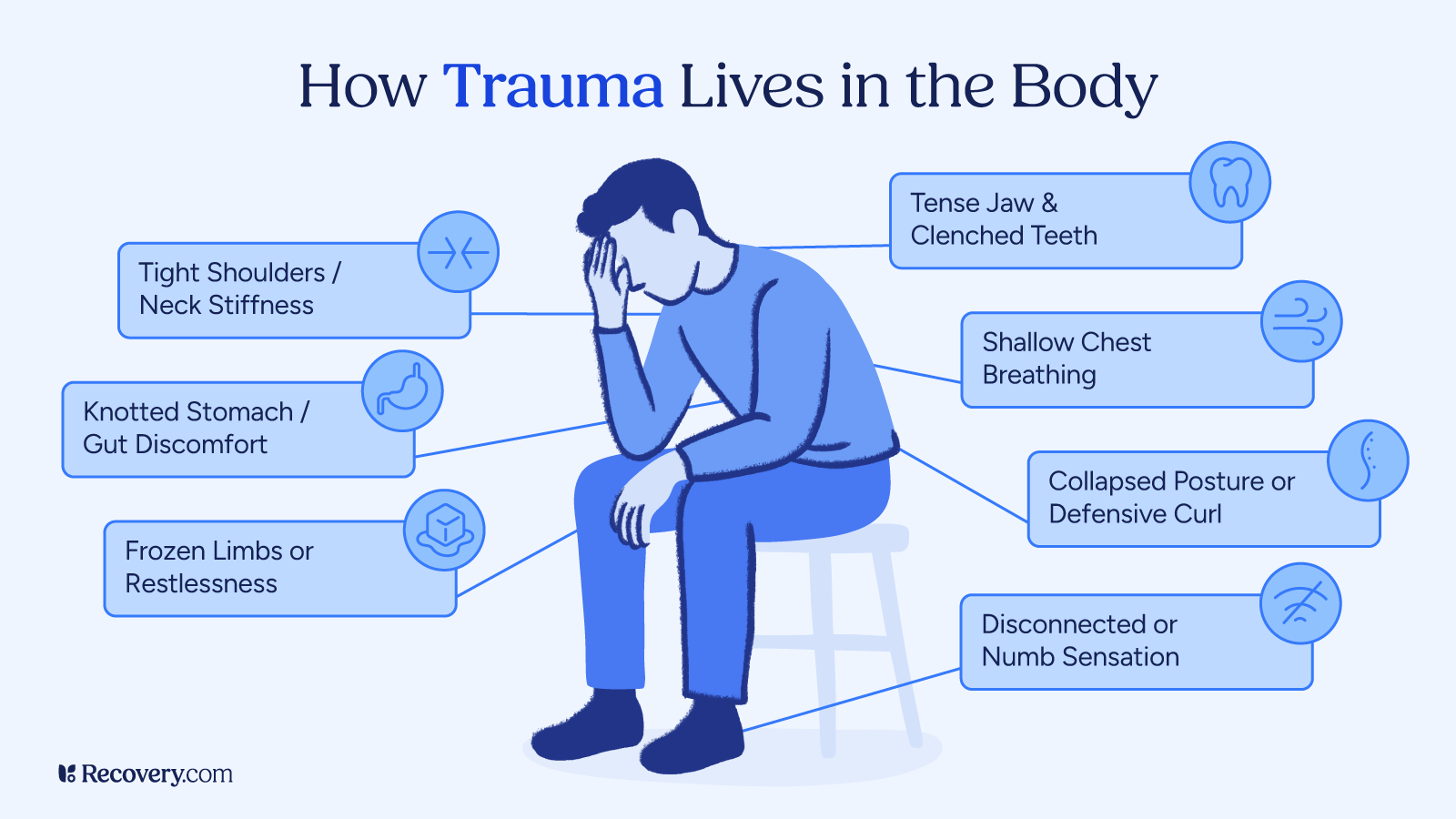

Davis’s feelings of not belonging started early in his life. He recalls being laughed at for his stutter as a child, which made him feel like an outcast. However, the most significant turning point came at the age of 10 when he was molested. This event solidified his mistaken belief system and became a secret he carried for decades. “That really hammered in that I’m faulty, that I’m dirty, that I don’t amount to much and I have no value in this world,” he says. This trauma, combined with the shame and secrecy surrounding it, became a powerful driver of his later addiction.

The experience created a deep sense of a loss of authenticity. Davis remembers feeling as if he wasn’t a “real man” because he couldn’t prevent the molestation, and he vowed that “no one can ever know” about it. This secret, this “stain,” as he called it, became a heavy burden that he tried to numb with drugs. His story highlights a critical link between unresolved childhood trauma and substance use disorders. Research has shown that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are a significant risk factor for developing addiction later in life1.

Explore trauma treatment options.

3. The “Addict” Ism Exists Long Before Substance Use Begins

Davis makes a powerful and somewhat provocative statement: he was a “drug addict before [he] ever picked up a drug or started drinking.” He explains that the addiction isn’t just about the substance; it’s about the feelings that drive a person to seek it out. For him, these were feelings of “uselessness,” an inability to control his “emotional natures,” and being “completely driven by fear.” He was struggling with these internal issues long before he took his first hit of marijuana at age 12.

When he finally did smoke that joint, it worked. For the first time, he felt a sense of belonging and comfort in his own skin. It was a “temporary solution” to a problem that had been festering for years. “I had the ism and I found the solution to it when I was 12,” he explains. This perspective challenges the common belief that addiction begins the moment someone first uses a substance. Instead, it suggests that the predisposition, or the “ism” of addiction, is an internal condition driven by emotional and psychological distress. The substance simply becomes the chosen—and ultimately destructive—tool for coping with that condition. This idea is supported by research into the bio-psycho-social model of addiction, which posits that a combination of genetic, psychological, and social factors contributes to the development of a substance use disorder.

4. The Physical Allergy and Mental Obsession of Addiction

For many people, the idea of an addict being unable to control their substance use is difficult to understand. They might think, “Why can’t they just have one drink?” or “Why can’t they just stop?” Davis explains this phenomenon using a concept described by Dr. William D. Silkworth, a physician who specialized in treating alcoholism in the early 20th century. Silkworth referred to it as a “physical allergy,” where consuming a substance “sets off what’s called the phenomenon of craving.” This craving is “beyond human comprehension” and compels the person to use more and more.

Davis vividly describes how this played out in his own life. He could tell himself he was only going to have one drink or smoke a little cocaine, but once the substance was in his system, a powerful craving took over, and he “lost the power of choice.” This physical craving is then compounded by a “mental obsession.” His mind would run “all these combinations about how this time is gonna work,” convincing him he could control his use, even though all his past experiences proved otherwise. He would “buy the lie again” and the cycle would continue. This mental obsession is a powerful force that can be difficult for non-addicts to comprehend. It’s not a matter of willpower; it’s a condition where the mind is essentially lying to the individual, telling them that this time will be different.

5. Selfishness in Addiction Is a Matter of Survival

When an addict’s behavior becomes destructive, their actions are often labeled as selfish. Davis acknowledges this, saying, “I mean, we are, I mean, everything is is about us.” However, he clarifies that this isn’t because addicts are “inherently just assholes.” Instead, he explains that it’s a function of being in survival mode. Many people with addiction, especially those with a history of trauma, are constantly in a state of fight-or-flight.

In this state, all a person can think about is their next move to get the relief they need. Davis recalls a deeply painful example of this from his own life. When his wife was in labor with their child, he drove her in the opposite direction of the hospital to meet his pill dealer. “I didn’t think anything of it,” he admits. This seemingly monstrous act was, to him, a necessary step in survival. His mind told him that if he didn’t get his pills, he would face an “unfathomable amount of pain and discomfort.” This fear, this need to avoid a feeling he couldn’t cope with, eclipsed all other considerations, including his wife’s pain and the birth of his child. This demonstrates how the self-centeredness of addiction is not a conscious choice to be cruel but an extreme, fear-driven response to a perceived threat to one’s well-being.

6. Desperation is the Catalyst for Change

For years, Davis went through a cycle of wanting to get sober and then relapsing. He went to treatment multiple times, but none of them stuck. He had the “want,” but he “lacked the willingness to do anything about it.” The reason for this, he realized, was that he hadn’t yet reached a state of true desperation. His family, in a misguided attempt to help, was unknowingly enabling his addiction by providing him with a safety net. “I knew that it wasn’t a sink or swim moment,” he says. Because he had options and knew he wouldn’t be completely on his own, he never fully committed to recovery.

This all changed when his family got educated on how to deal with his addiction. They intervened and gave him a clear choice: go to a long-term treatment center with no discharge date or go to jail. When he tried to leave the program two months in, he called his dad for a bus ticket, hoping for the same enabling support he had always received. But this time, his dad said, “No. Figure it out. Love you. Bye.” That was the moment everything shifted. “That was my life-changing moment,” he recalls. This “gift of desperation” provided the pain he needed to fully surrender and become willing to do the hard work of recovery.

7. The Gift of Time and the Power of Accountability

Davis’s last treatment experience was unlike any of the others he had been through. He describes it as the “Navy Seals of treatment centers,” designed for individuals “reluctant to recover.” One of the most critical differences was the removal of a discharge date. In his previous programs, the limited time frame gave him a sense of an end date, which prevented him from truly surrendering. In this program, with no end in sight, he was forced to face himself. “You’re gonna tell if somebody’s compliant or surrender very quickly when you take the discharge date off,” he notes.

This extended stay, which lasted nearly a year, gave him the “gift of time.” It allowed him to build a solid foundation for his recovery, going through the ups and downs of early sobriety in a structured, safe environment. The program also provided “excellent clinical care that processed the experience of an immersive 12-step experience.” Unlike other programs where he was just given worksheets, this one spoon-fed him the principles of the 12 Steps from day one. He was held accountable by both staff and his peers, which forced him to confront his past behaviors and develop new, healthier ones.

8. Recovery Is an Experience, Not Just Information

Before his final treatment, Davis went through several programs but left “just as confused about what my problem was than when I went in the door.” He had been given clinical information and worksheets, but no real experience of recovery. He explains, “sober isn’t about information. It’s about an experience.” His final program was different because it allowed him to experience what it felt like to be sober and to live by a new set of principles.

Through the intensive 12-step process, he was able to rebuild his “internal constitution” and realign his moral compass. For the first time, he experienced what it felt like to have peace without the use of drugs. He started to see glimpses of the solution and not just the problem. This experience gave him a powerful motivation to continue. He realized that the promises of recovery were not just “marketing material” but a reality he could achieve. This desire for more of that feeling—more peace, more clarity, more freedom—is what kept him going even when he wanted to give up.

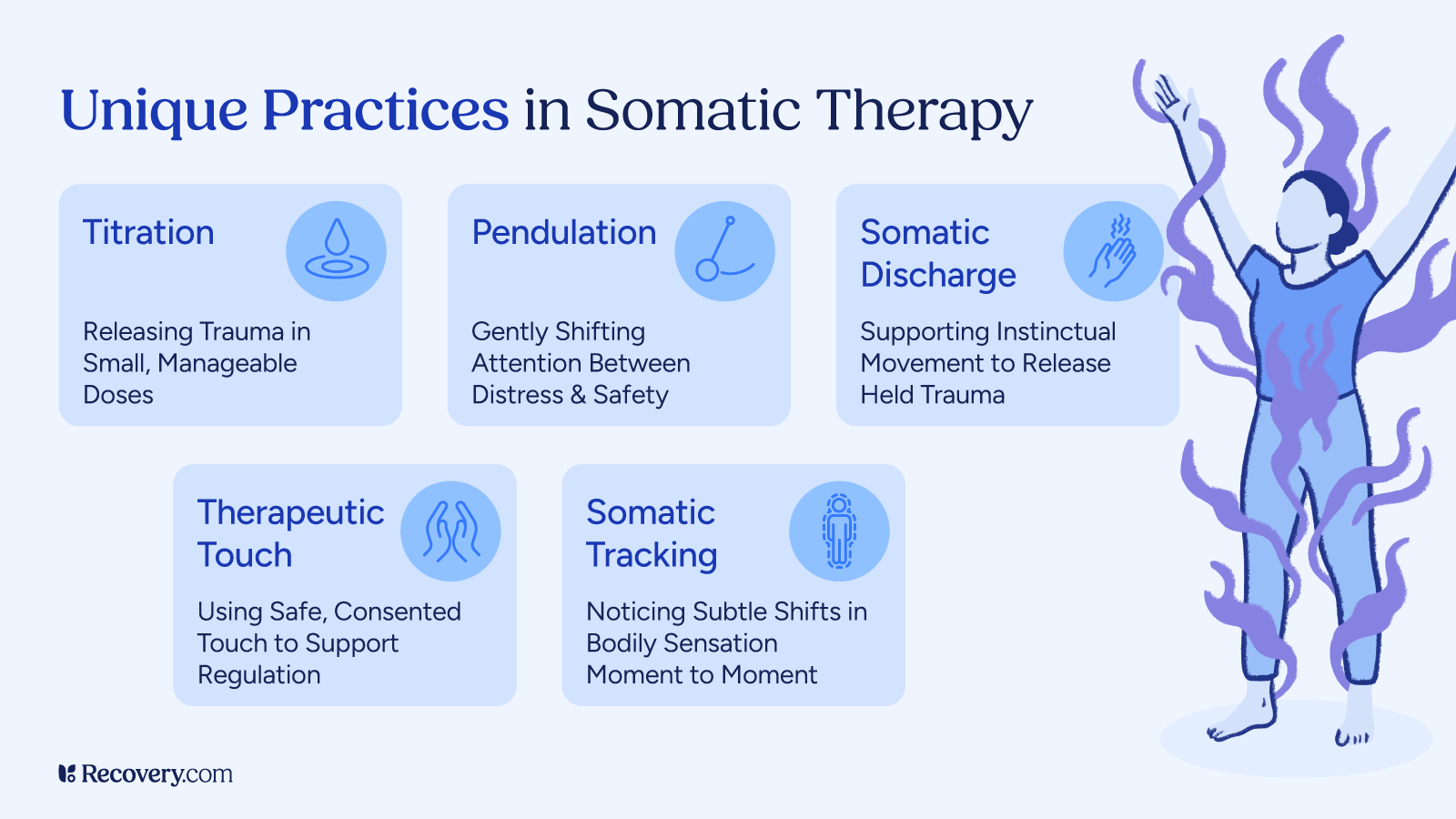

9. Finding Freedom Through Challenging Core Beliefs

Davis spent years with the trauma of his childhood molestation, convinced it was a secret he would take to his grave. In recovery, he was finally able to face it, but not in the way he had expected. He didn’t have to “live through the whole thing” again. Instead, he went through a trauma intensive workshop that challenged his core belief systems. “It challenged a core belief that I had about myself and the world around me,” he explains. He came to accept that the belief he was “faulty” was not a fact, and by dismissing it, he opened the door for new, healthier beliefs to take root.

This process was about taking responsibility for his life, not for the trauma itself. He explains this through the lens of the 12-step inventory, which asks a person to look at their “part” in a situation. As a 10-year-old, he had no part in the molestation itself, but he was responsible for “how I let it dominate my life” from that point on. By accepting this responsibility, he was able to move past the victim mentality and begin to heal. This new perspective gave him a profound sense of clarity and freedom.

10. The Freedom of Knowing You Can Overcome Anything

Today, Davis lives a life of peace and freedom that he never thought possible. When asked what that freedom feels like, he shares a deeply profound realization: “I know that there is nothing in this life that is going to come down the road at me that is going to be more painful or more challenging than what I’ve come through.” He has confronted his deepest fears and traumas and survived the hellish years of his active addiction.

This perspective gives him a sense of unwavering strength and resilience. He knows that no matter what life throws at him—tragedy, loss, or illness—he has the internal tools and the foundation to handle it. This realization is a testament to the power of a long-term, comprehensive recovery process. It’s not just about abstaining from substances; it’s about building a life that is so strong and so fulfilling that you no longer need an escape.

11. Don’t Just Go to Rehab; You Get to Go to Rehab

For those who are just beginning their journey, Davis offers a simple yet transformative piece of advice: look at the content the algorithms are showing you. If you’re seeing a lot of recovery-related material, “the algorithm’s trying to tell you something.” He encourages people to see rehabilitation not as a punishment but as a gift. “You don’t got to, you get to,” he says.

He frames the opportunity to unplug from the world and do deep emotional work as a privilege, not a chore. He encourages people to “take care of your emotional health” and to challenge the stories they tell themselves about why they can’t get better. By shifting this perspective, a person can move from a place of resistance to a place of willingness, making it far more likely that they will find the desperation and surrender needed for long-term recovery.